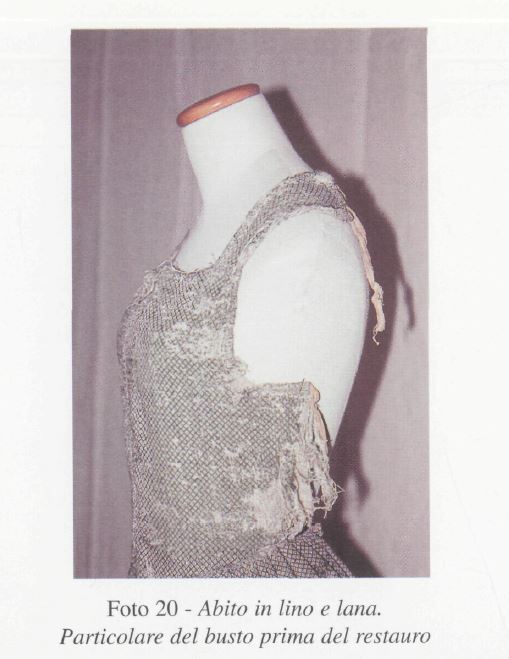

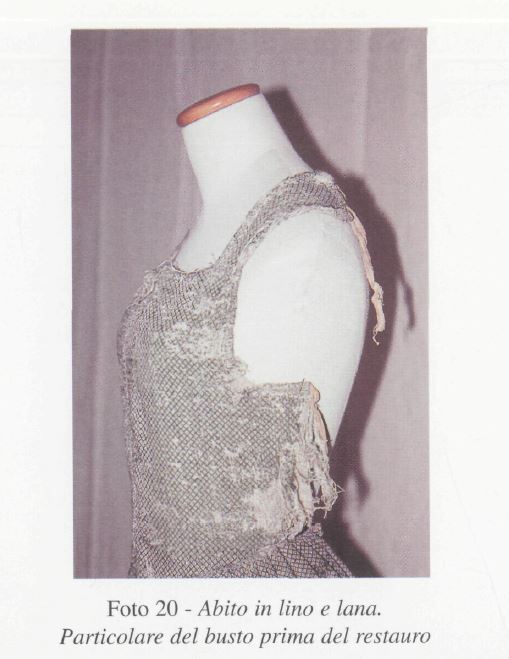

Bodice of a gown worn by by a servant of Eleanora de Toledo. Taken from the book La Granduchessa.

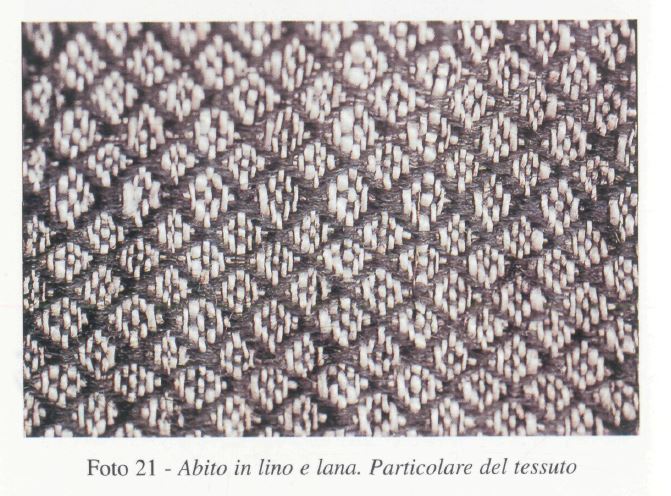

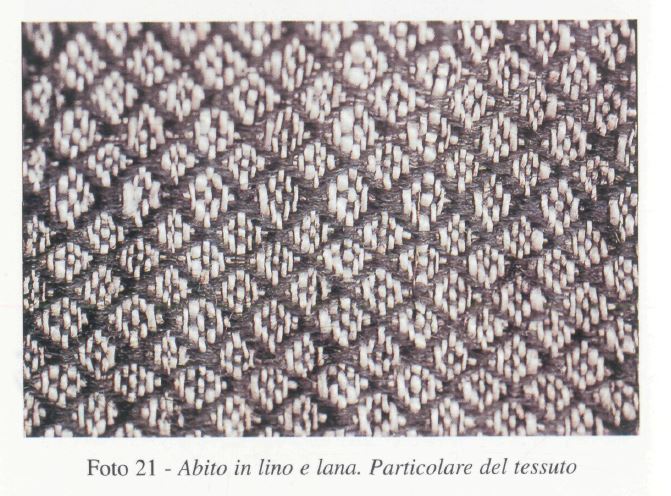

Close-up of the mixed linen-and-wool fabric worn by a servant of Eleanora de Toledo. Taken from the book La Granduchessa.

This waistcoat and petticoat are representative of what a fairly well-to-do goodwife would have worn at the turn of the 17th century.

The waistcoat is patterned upon the waistcoat in Janet Arnold's Patterns of Fashion 1560-1620. Additional inspiration came from images of women's waistcoats in the Trevelyon Miscellaney of 1611. I chose this handwoven fabric due to its similarity to a green-and-cream birdseye twill used in a mid-16th century Italian Serving woman's bodice. The fibre of my waistcoat, however, is cotton.

Bodice of a gown worn by by a servant of Eleanora de Toledo. Taken from the book La Granduchessa.

Close-up of the mixed linen-and-wool fabric worn by a servant of Eleanora de Toledo. Taken from the book La Granduchessa.

Although such fabric wasn't as esteemed as the other mixed linen-and-wool fabrics that made up some of the "New Draperies" popular in England at the time, such fabric would have been made and sold locally in small English towns.

The waistcoat is lined with an unbleached linen fabric, and is trimmed with a narrow band of wool tape. The tape, originally white, I dyed red with brazilwood using a recipe for red from the 16th century dye-book "The Plictho". Simple wool tape, or "lace" as it was called, was frequently used to trim seamlines, shoulder epaulets, and other garment edges at the end of the 16th century.

The petticoat is made of red wool. The fabric is admittedly finer that a woman of modest means could have afforded in 1600; it closely resembles scarlet broadcloth, a pricey, high-quality wool used in the petticoats of the better-off merchant class and nobility. The pattern for the petticoat comes from a c. 1600 petticoat in Janet Arnold's Patterns of Fashion 1560-1620. The pleats are interlined with a layer of heavy wool to aid in shaping and in achieving the proper silhouette, a practice frequently referred to in wardrobe accounts and tailor's bills of the late 16th century.

The jacket and petticoat combination, worn over a smock and with or without boned bodies underneath, was the standard dress of workaday women at the turn of the 16th century.

The jacket and petticoat combination, worn over a smock and with or without boned bodies underneath, was the standard dress of workaday women at the turn of the 16th century.

Waistcoats could button up the front, tie together with ribbons, be pinned together, be fastened with hooks and eyes, or fastened with lacing rings. All of these methods are seen in extant waistcoats of the time or in paintings of women wearing waistcoats. My waistcoat fastens with lacing rings up the front, with a lace run through them.

Waistcoats could button up the front, tie together with ribbons, be pinned together, be fastened with hooks and eyes, or fastened with lacing rings. All of these methods are seen in extant waistcoats of the time or in paintings of women wearing waistcoats. My waistcoat fastens with lacing rings up the front, with a lace run through them.

Jackets of this style did not have darts or princess seams to handle shaping around the bust area. Shaping was accomplished by a curved front seam and clever shaping of the armescye curve and side-back seam. Some doublets had the armscye eased into the sleeve head and the front shoulder seam stretched to fit the back in order to shape the shoulder area more closely to the body.

Jackets of this style did not have darts or princess seams to handle shaping around the bust area. Shaping was accomplished by a curved front seam and clever shaping of the armescye curve and side-back seam. Some doublets had the armscye eased into the sleeve head and the front shoulder seam stretched to fit the back in order to shape the shoulder area more closely to the body.

This jacket does not have a collar at the back, although some jackets did at the time. The collar was used to help prop up a ruff.

This jacket does not have a collar at the back, although some jackets did at the time. The collar was used to help prop up a ruff.

The red lace is stitched down over most of the seams on the garment.

The red lace is stitched down over most of the seams on the garment.

The wide flare at the waist of the jacket was necessary to accomodate the bulky petticoats of the time.

The wide flare at the waist of the jacket was necessary to accomodate the bulky petticoats of the time.

At the turn of the century, jackets like this one sat at the natural waist. As the 1600s became the 1610s and 1620s, the waistline rose to mid-rib.

At the turn of the century, jackets like this one sat at the natural waist. As the 1600s became the 1610s and 1620s, the waistline rose to mid-rib.

When sewn in correctly, lacing rings are invisible. At a distance,it can almost look like another seamline.

When sewn in correctly, lacing rings are invisible. At a distance,it can almost look like another seamline.

The sleeves are sewn into the armescye with a backstitch, the excess turned down and a sleeve lining of unbleached linen stitched over the raw edges. Seam allowances in garments of the time were narrower than they are today; 1/4 to 3/8 of an inch was common.

The sleeves are sewn into the armescye with a backstitch, the excess turned down and a sleeve lining of unbleached linen stitched over the raw edges. Seam allowances in garments of the time were narrower than they are today; 1/4 to 3/8 of an inch was common.

PERIOD STRYP-TEESE!

PERIOD STRYP-TEESE!

Shillings goe here. I prithee, Give thou Generousely!

Shillings goe here. I prithee, Give thou Generousely!

The lacing rings are visible here. If the jacket is very tight, all rings are neaded to avoid gapping in the front; it is fairly loose on me, so I lace up with every other ring. The fabric stretches quite a bit and molds well to the body with few wrinkles, even when it's laced tight.

The lacing rings are visible here. If the jacket is very tight, all rings are neaded to avoid gapping in the front; it is fairly loose on me, so I lace up with every other ring. The fabric stretches quite a bit and molds well to the body with few wrinkles, even when it's laced tight.

The petticoat is bound with a narrow band of black silk taffeta at the waist. It sits about an inch lower than my natural waist; I find this most comfortable when wearing it with jackets.

The petticoat is bound with a narrow band of black silk taffeta at the waist. It sits about an inch lower than my natural waist; I find this most comfortable when wearing it with jackets.

The points along the waist of the french bodies are used to tie the petticoat to the bodies. This transfers the weight of the skirts from the waist to the torso, making them feel lighter. It also keeps the skirt from slipping down or rotating.

The points along the waist of the french bodies are used to tie the petticoat to the bodies. This transfers the weight of the skirts from the waist to the torso, making them feel lighter. It also keeps the skirt from slipping down or rotating.

This petticoat laced closed at the back. The pleats are knife pleats, with a layer of wool pleated in with the outer fabric. The waistband is bound around the raw edges of the pleats.

This petticoat laced closed at the back. The pleats are knife pleats, with a layer of wool pleated in with the outer fabric. The waistband is bound around the raw edges of the pleats.

A point laces through two holes on either side of the petticoat's back opening. This allows for considerable adjustability. Also, when the laces are tied together after being threaded through both sets of holes, they stay laced remarkably well--it takes work to loosen the hitch.

A point laces through two holes on either side of the petticoat's back opening. This allows for considerable adjustability. Also, when the laces are tied together after being threaded through both sets of holes, they stay laced remarkably well--it takes work to loosen the hitch.

Here is a view of the layer of wool used to interline the pleats.

Here is a view of the layer of wool used to interline the pleats.